Hercules Mulligan, an Irish immigrant, became an unsung hero of the American Revolution. Though the musical ‘Hamilton’, whose chief goal is to entertain, has introduced his name to a broader audience, Mulligan’s real contributions as a spy and hero of American independence are far more compelling than the play suggests.

Mulligan was born in Coleraine, Co Derry, in 1740 and emigrated with his family to North America at the age of 6, settling in New York City. He attended King’s College (now Columbia University). Mulligan opened an upscale tailor shop. While he had several tailors on staff, the charismatic Hercules made it a point to serve and fit every customer personally. The level of service soon made Mulligan’s shop a favorite of New York’s elite, particularly British officers who would have Mulligan tailor their uniforms.

While comfortably placed in Colonial British social circles, it did not reflect Mulligan’s beliefs as an ardent proponent of American independence. Mulligan was a founding member of the New York Sons of Liberty, a clandestine group established to defend the colonists’ freedoms from increasingly restrictive British regulation. He was a New York Committee of Correspondence member, which attempted to unify and coordinate opposition to British rule throughout the colonies.

It was about this time that Hercules’ brother Hugh, who ran a shipping firm, introduced him to Alexander Hamilton, a young man who had recently arrived from the West Indies. Hercules took the young Alexander in as a border and soon developed a close friendship; Mulligan arranged for Hamilton to attend his alma matta Kings College/Columbia. Conversations at the Mulligan table persuaded Alexander Hamilton to make the rebel cause his own.

When Washington’s army evacuated the city of New York, Mulligan was initially detained, though released, and found himself an American patriot in one of the strongest areas of loyalty to the Crown in the colonies. Mulligan returned to continue his business at his tailor shop until he received word that on the recommendation of Alexander Hamilton, now an officer on Washington’s staff, Washington was asking him to take on the dangerous role of spy. Mulligan accepted at once.

Mulligan proved extremely successful as a spy. In his shop’s relaxed, unoffensive atmosphere, British officers frequently let their guard down with the charming Irishman and reveal more than they should. When multiple officers came into his shop saying they needed delivery on the same date, Mulligan would communicate that troop movements were imminent. His brother Hugh, whose shipping company was now delivering supplies for the British, was also a valuable source of information. Mulligan would send these messages across enemy lines using his slave Cato as a courier, playing on the fact that as an enslaved person, the British would ignore him,

On two separate occasions, information supplied by Mulligan is credited in saving Washington’s life. In one incident, a British soldier came rushing into Mulligan’s shop after hours to buy a new watch cloak. When Mulligan asked why the late hour and rush, the officer couldn’t contain himself, he told him excitedly that he was part of a mission to kidnap Washington. Mulligan quickly sent word to Washington, and the kidnapping plan was thwarted. The second incident occurred in 1781 when his brother’s import-export firm received a large rush order that revealed plans to capture Washington in Connecticut while traveling to Rhode Island to meet with the French. Again, Mulligan’s intelligence warned Washington to change his route.

Mulligan’s activities were not without risk. He had already been interrogated twice on suspicion of spying but had been able to charm his way out of it. However, he was directly betrayed by Benedict Arnold. However, Arnold’s lack of hard evidence and the likely general disdain amongst the British Officers for the word of a traitor allowed Mulligan to escape prison, but his usefulness as a spy was over.

However, Mulligan’s greatest threat was from his fellow New York Patriots, who thought he was a British collaborator and, ironically, a spy for the British. The fear of reprisals against himself and his family could not have been far from Mulligan’s mind as the British evacuated and Washington’s troops marched into the city. However, Washington did not forget Mulligan or his service; as soon as he accepted the British surrender of the city, Washington made a very public visit to Mulligan to have breakfast at his home, sending a clear message that Mulligan was a patriot.

Washington continued to repay Mulligan, placing several orders with him, allowing Mulligan to promote himself as “the official tailor to General Washington” and later “President Washington.” Mulligan became one of the 19 founding members of the New York Manumission Society, an early American organization that promoted the abolition of slavery.

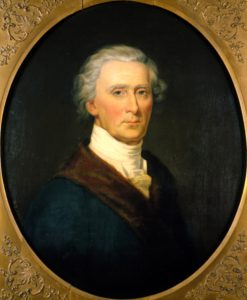

The real Hercules Mulligan deserved to be better known. Sadly, while the play “Hamilton” has made his name known, the man and his deed remain hidden. In perhaps an ultimate indignity, in response to the notoriety the play had given Mulligan, a story on an internet website showed a painting purporting to be Mulligan. This image of “Hercules Mulligan” has spread across the internet as other articles, even historical sites, have mindlessly parroted. The only problem: it is a painting of Charles Carroll, the signer of the Declaration of Independence.